About PDA

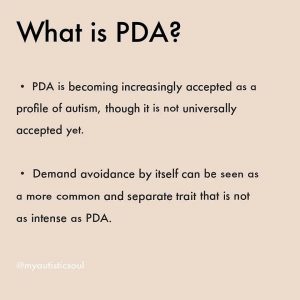

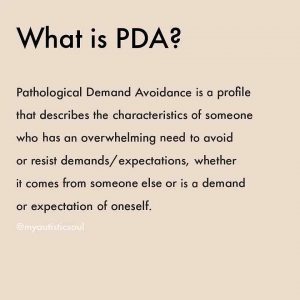

Pathological demand avoidance (PDA) is a proposed subtype of Autism Spectrum Disorder but is not yet recognised by the DSM-5 and may be unlikely to be given the umbrella diagnosis of 'ASD' has been adopted (and removed Asperger’s Syndrome).

PDA is a fairly new and unrecognised condition in the field, making diagnosis and support challenging.

The Autistic community is campaigning to have this subtype of Autism to be re-named Pervasive Drive for Autonomy, as the term Pathological Demand Avoidance assumes that the person is purposefully being controlling and manipulative and ignores that anxiety is the root cause.

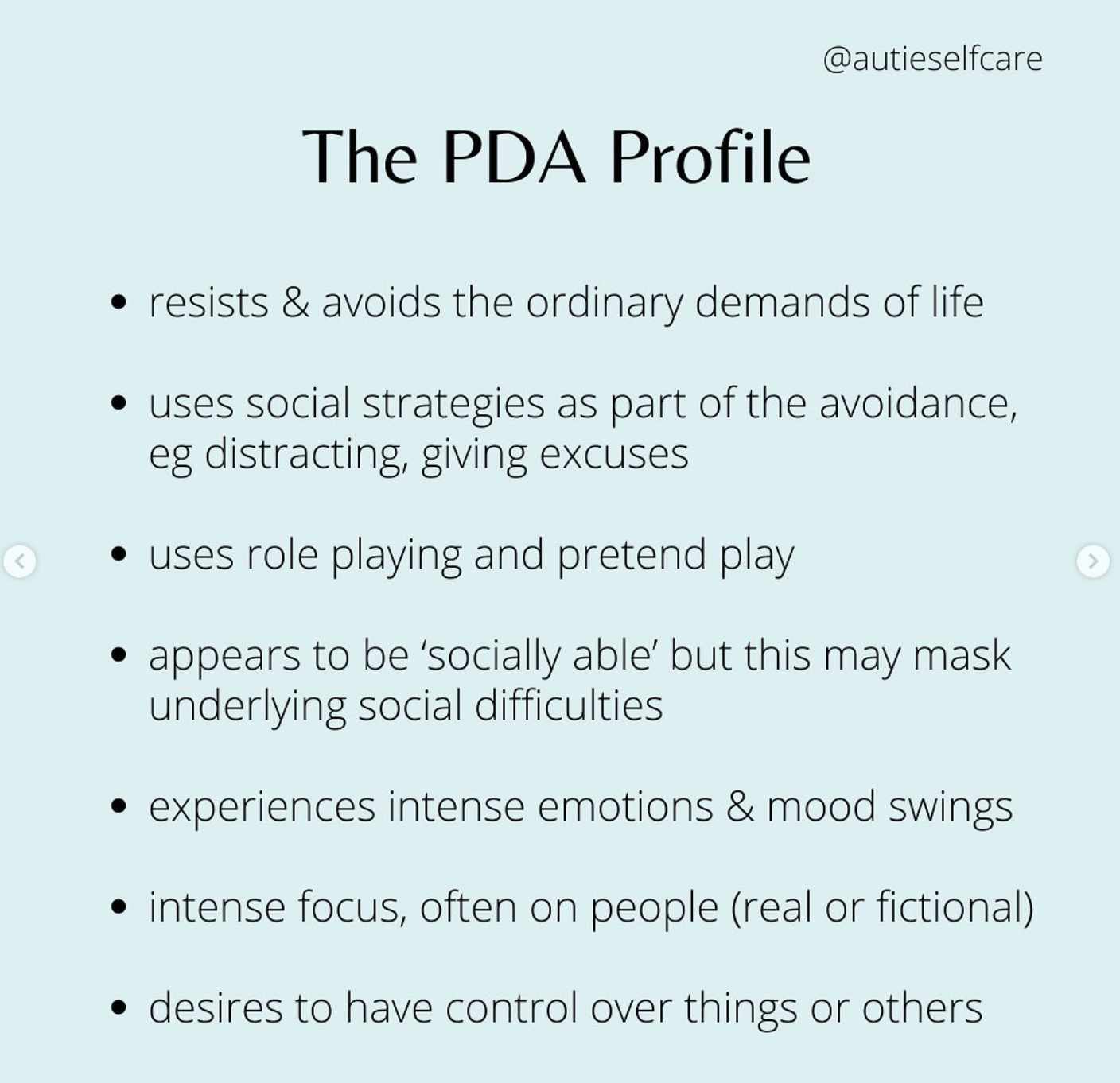

Source: @autieselfcare, 'The PDA Profile'

Those with a demand avoidant profile share difficulties with others on the Autism Spectrum in social communication, social interaction and restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviours, activities or interests. However, those who present with this particular diagnostic profile are driven to avoid everyday demands and expectations to an extreme extent.

It may appear as though someone with PDA has better social understanding and communication skills than others on the Autism Spectrum and are able to often use this to their advantage. Although children with PDA seem to socialise well, have fair eye contact, and are able to mask their weaknesses pretty well on the surface, their underlying social skills and ability to read social situations are poor, as more recent research into this condition has determined.

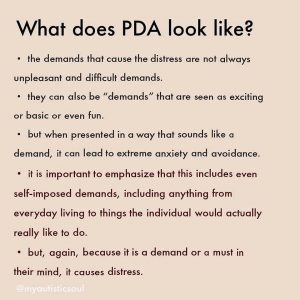

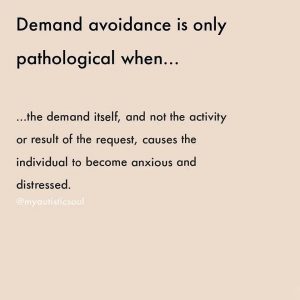

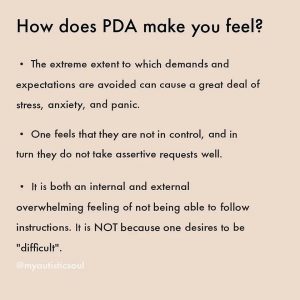

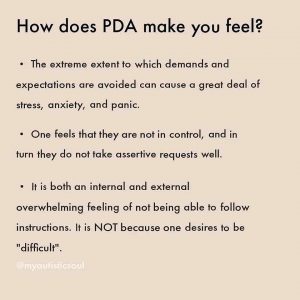

The demand avoidant behaviour is rooted in an anxiety-based need to be in control as research has shown that underneath the strong social façade and pretence is a person who feels very inadequate, scared, and insecure. The anxiety and fear control every aspect of their daily life. The need to control everything, following nothing, and avoid all daily demands is driven by this anxiety and strong feelings of inferiority.

Life becomes too scary and overwhelming that they often mix reality with fantasy to create a world that they feel safe and competent. This usually means refusing to follow anyone else’s guidance, since to do so leaves them vulnerable to uncertainty and increased anxiety. This is not just common anxiety, but a deep-rooted fear.

Those with PDA often make up elaborate reasons to avoid requests, demands and any expectations (they are sick, too smart for something that stupid, will do it later, redirect peoples attention elsewhere, etc.) They even find it hard to meet their own desires and expectations., eventually withdrawing into a defensive mode of avoiding all meaningful life activities that parents and others try to coax or demand them into doing.

Unfortunately, most adults (parents, teachers, professionals) view them as defiant, manipulative, and purposely oppositional, which only fuels their need to command and demand even more.

- Resists and avoids the ordinary demands of life

- Uses social strategies as part of avoidance, e.g. distracting, giving excuses

- Appears sociable, but lacks understanding

- Experiences excessive mood swings and impulsivity

- Appears comfortable in role play and pretence

- Displays obsessive behaviour that is often focused on other people.

People with this profile can appear controlling and dominating, especially when they feel anxious. However, they can also be enigmatic and charming when they feel secure and in control.

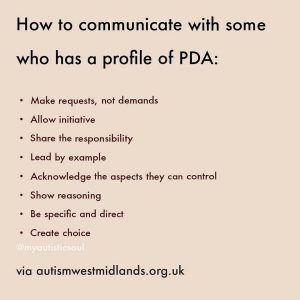

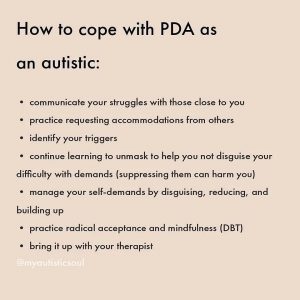

Supporting those with PDA is extremely challenging, as they can too easily become more resistant and sophisticated in their avoidance, sabotage everything that looks like external control, even refuse to do what they like if others are requesting it. Pressure only pushes them further into being defiant and not trusting the guidance of others. Only by backing off the demands, letting them control and trust that you will let them, and gradually building a collaborated relationship with them, can you lessen the anxiety and build more trust in your guidance.

Children with PDA are the most complex and vulnerable children to help. They resist almost every parenting, teaching, and disciplinary technique common to children. The harder you try to help (by instructing, directing, prompting, etc.) the more they resist, the more they act out and the further away they become from feeling safe with others. Very frustrating and heartbreaking for parents and teachers.

When you try to reverse your strategies to a low-demand, collaborative, working partnership model, you are chastised by other parents, family, teachers, and professionals.