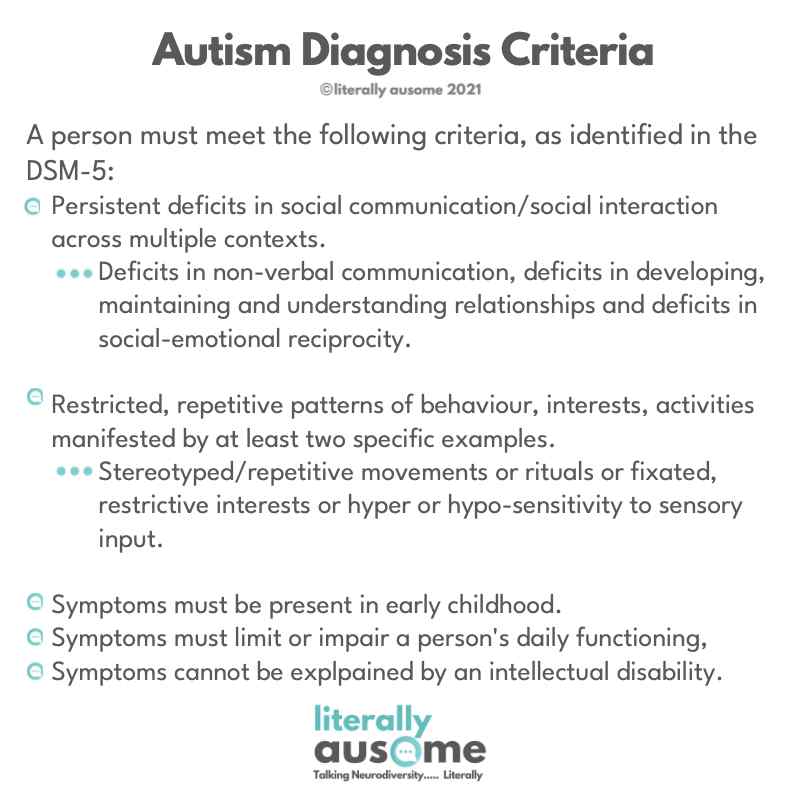

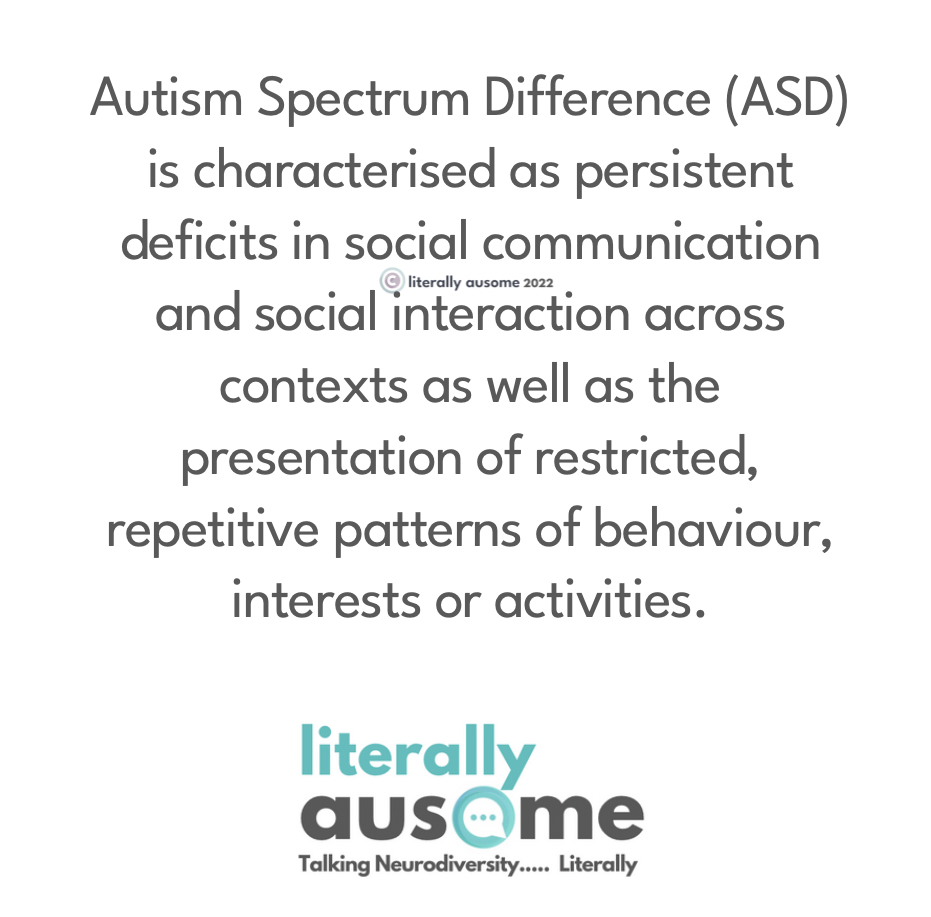

Autism Spectrum Difference (ASD*)

Autism Spectrum Difference (ASD) is characterised as persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts as well as the presentation of restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities.

For a child to be diagnosed as Autistic*, they need a team of experts (Psychologist, Speech Therapist and Paediatrician) that refer to a 'checklist of traits' or 'characteristics' from the DSM-V/DSM-5 - the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Ed.

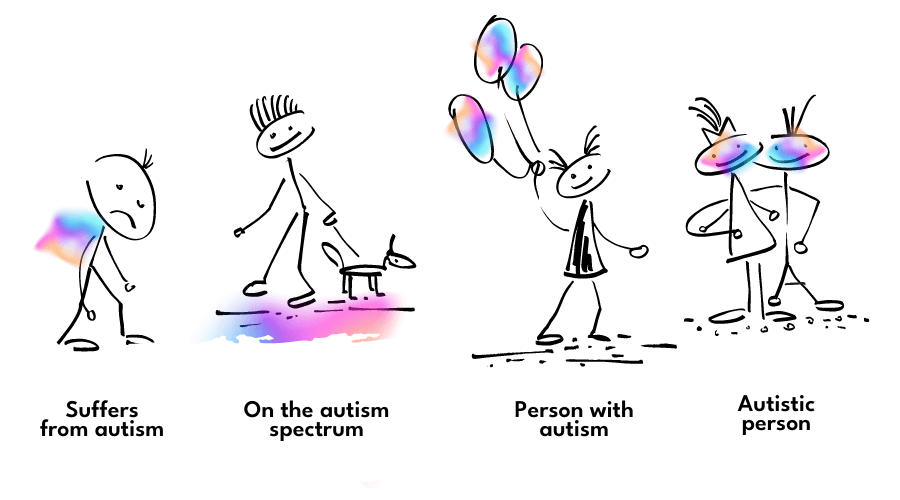

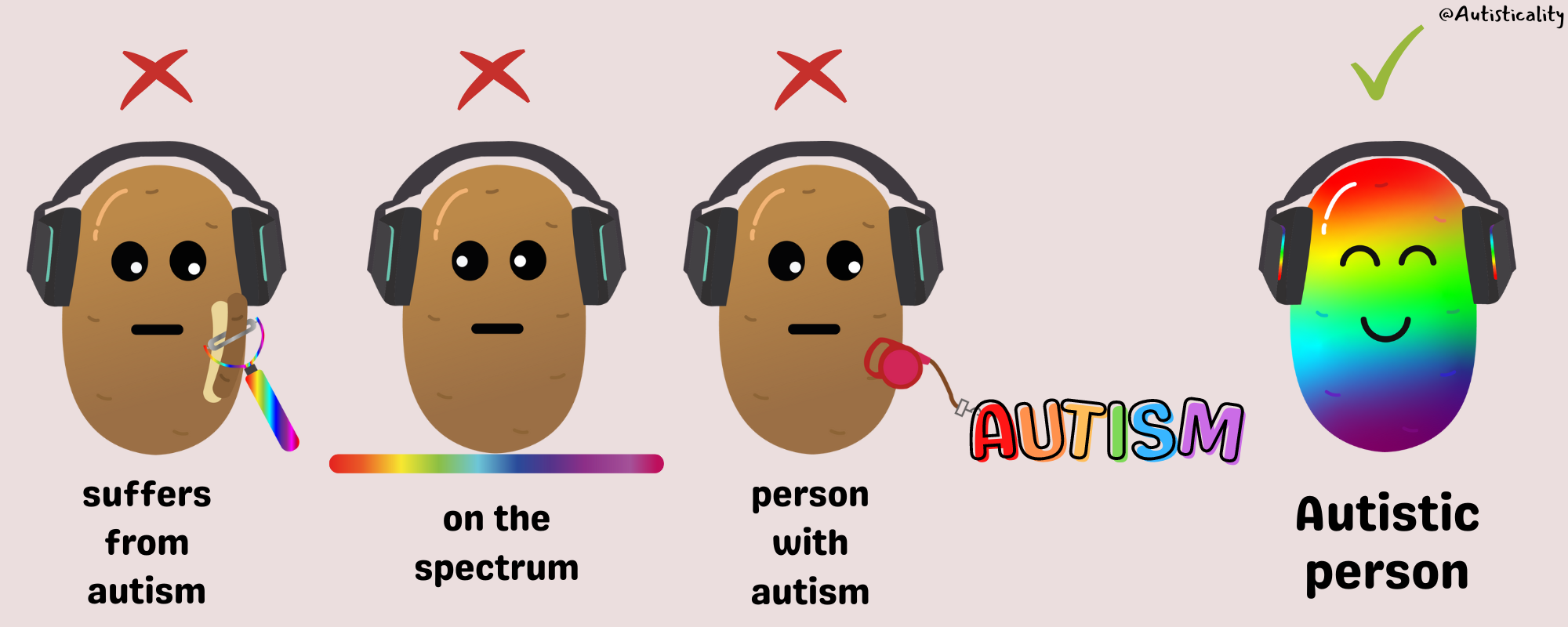

*Autistic people have been advocating for the name of this condition to change from Autism Spectrum Disorder as the term Disorder is offensive. There are some that would like to see the name change to 'Autism Spectrum Condition', but in the meantime with the 'D' still in the title and acronym, the term 'Difference' is being used.

These characteristics have been used for many years, and are mainly based on a male/boy's presentation of Autism, as experts believed that only boys/males could be Autistic. This makes it much harder for girls/females to be diagnosed (see the section below on the female presentation of Autism.

Source: Understanding The Spectrum – A Comic Strip Explanation, Rebecca Burgess

The Mighty

The Art of Autism

The Autism Diagnostic Criteria - The Autistic Community's Response

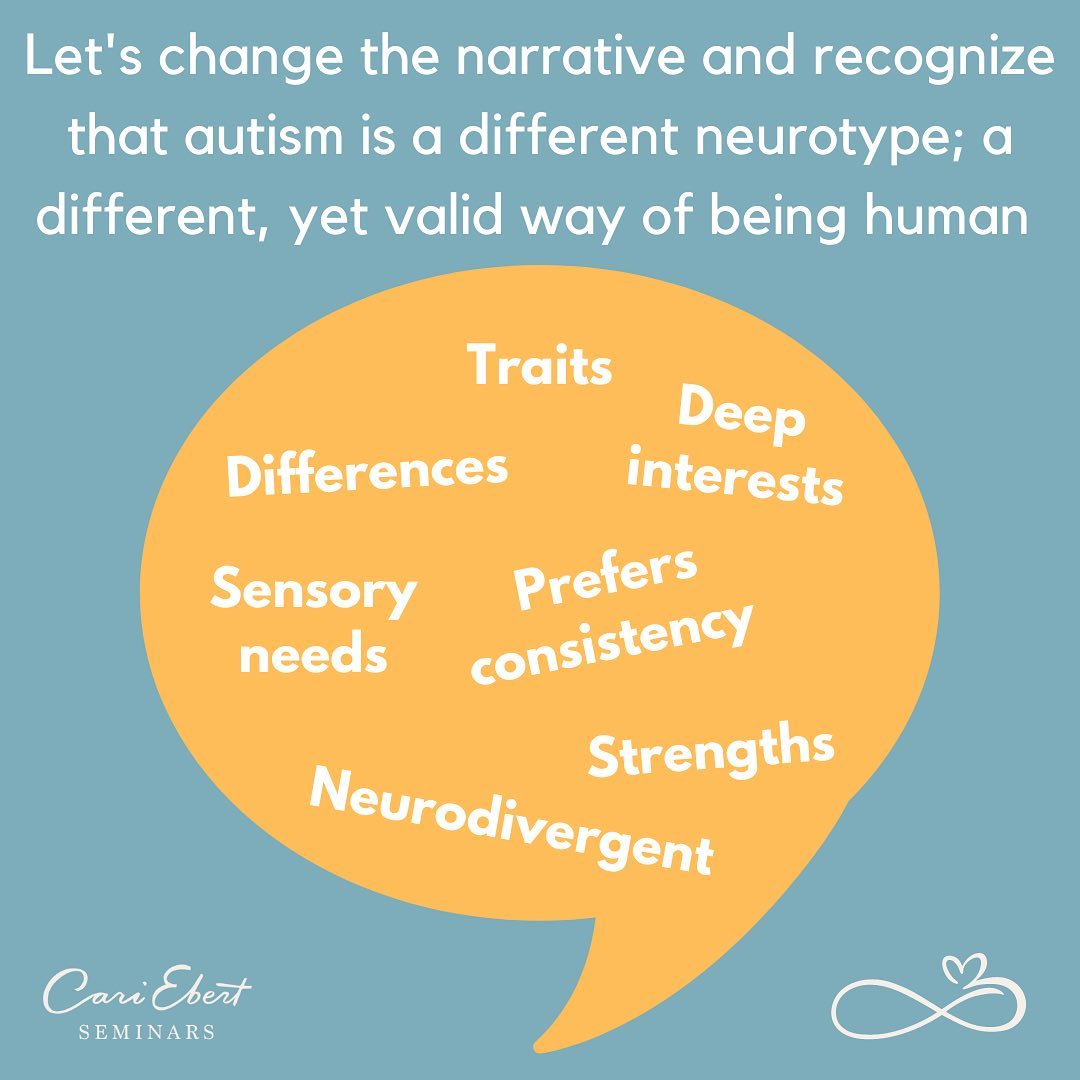

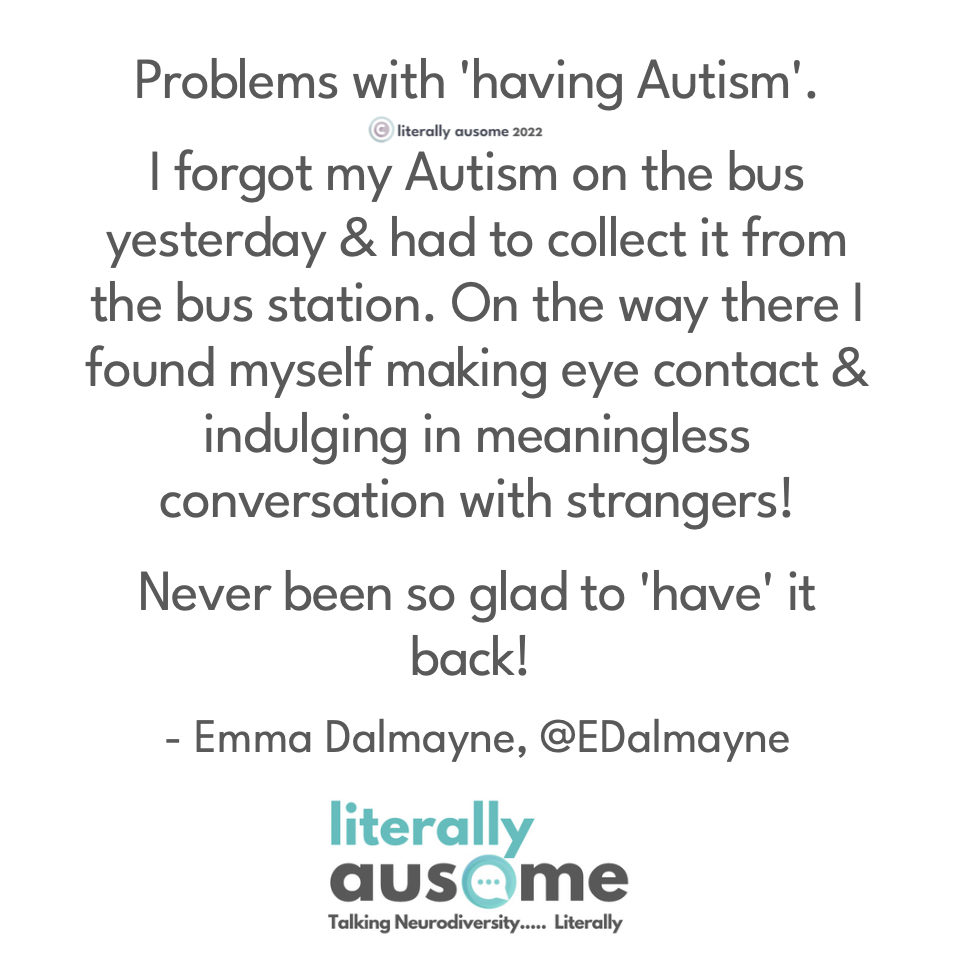

There are many Autistics who don't feel comfortable with the wording of the diagnostic criteria, as it focuses on problems and challenges, using words like 'deficits' and 'failure' and is a very negative portrayal and explanation of what Autism is.

The terminology also defines Autistic socialising as wrong or disordered, but from the Autistic person's perspective, it's just 'different' socialising. This assumption and the use of negative terms are both offensive and hurtful to the Autistic community.

The criteria also views Autism as a behavioural condition which is also incorrect as we know it's neurological. It also fails to recognise other areas that impact Autistic people such as sensory processing/sensory sensitivities.

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities

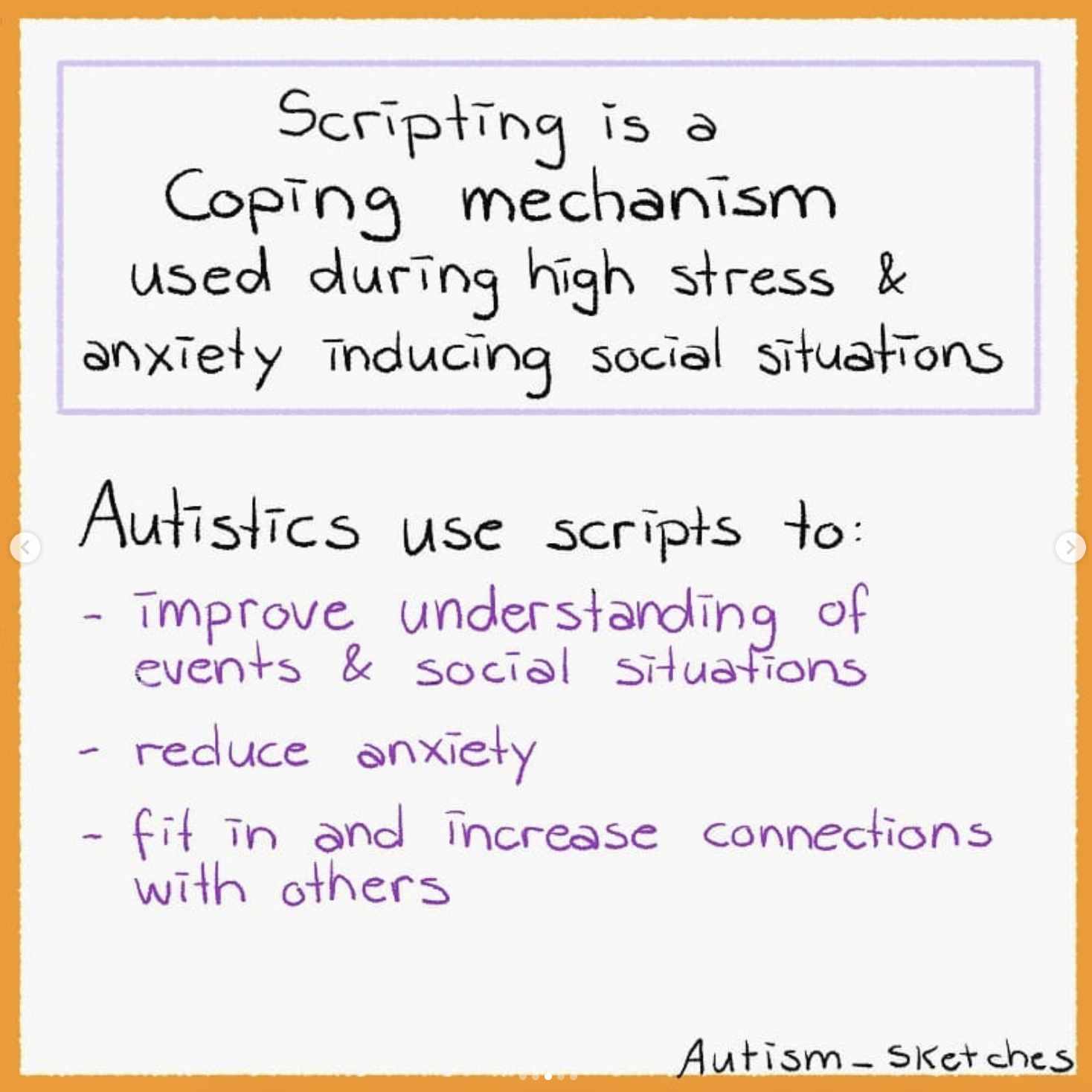

The following routines/schedules and patterns for both verbal or non-verbal behaviour.

- Verbal refers to repeating the same words, phrases or even sounds over and over again (called 'echolalia').

- Non-verbal refers to needing predictability (knowing what's going to happen in the near future) and also insisting on doing the same things over and over and exactly the same way each time. Autistic people have daily routines, schedules and rituals that make them feel comfortable and in control as well as insisting on following the rules (and letting you know when you've broken them).

Autistic people tend to feel more anxious than Neurotypicals, including feeling overwhelmed, worried, confused, or a combination of these emotions. A way of helping themselves stay calm is liking to know what's happening and having things as predictable as possible. This helps them feel in control and able to deal with the things that are more challenging.

- 'Unexpected changes' to plans, or when things don't happen the same way as they previously did can be really distressing and difficult to cope with and also might result in a meltdown or shutdown and not be able to participate in events, class, or celebrations etc.

- Repetitive behaviours also refer to certain movements or noises that your friend may do to keep themselves calm. This is called 'stimming' or self-soothing/self-stimulating behaviours. An example of stimming that your friend may do, and something we all do really, to keep ourselves calm or relaxed is play with fidget toys, twirl our hair, swing our legs under a desk or table or stretch our shoulders when feeling pressured or stressed.

- We all stim, but sometimes Autistic stims are more obvious, might be practised more often or done in settings that might seem inappropriate like clicking their knuckles during a 'minutes silence'.

This refers to hobbies and/or actions that may look and/or sound obsessive or intense to others but is also how an Autistic person keeps themselves calm.

These are usually subjects or topics that are called 'special interests' or hobbies and have also been called obsessions when the person is completely absorbed in their special interest and might talk incessantly about them. It also wouldn't be unusual for them not to be interested in anything other than their favourite topics, even if everyone else is.

Restricted and Repetitive Behaviour Explained

When your friend shares their interests with you over and over again, it might be really annoying.

Try to remind yourself that it's the way your friend or peer is trying to connect with you.

Links

The Autism Spectrum

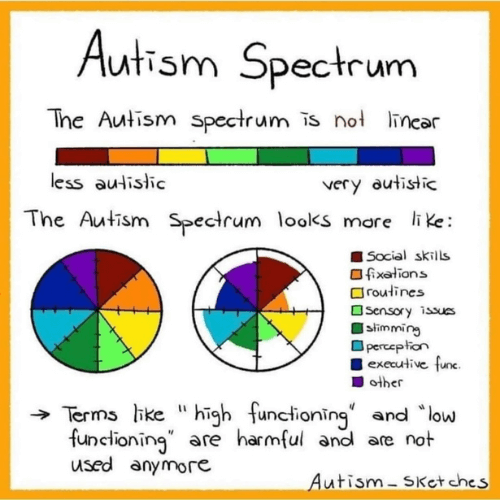

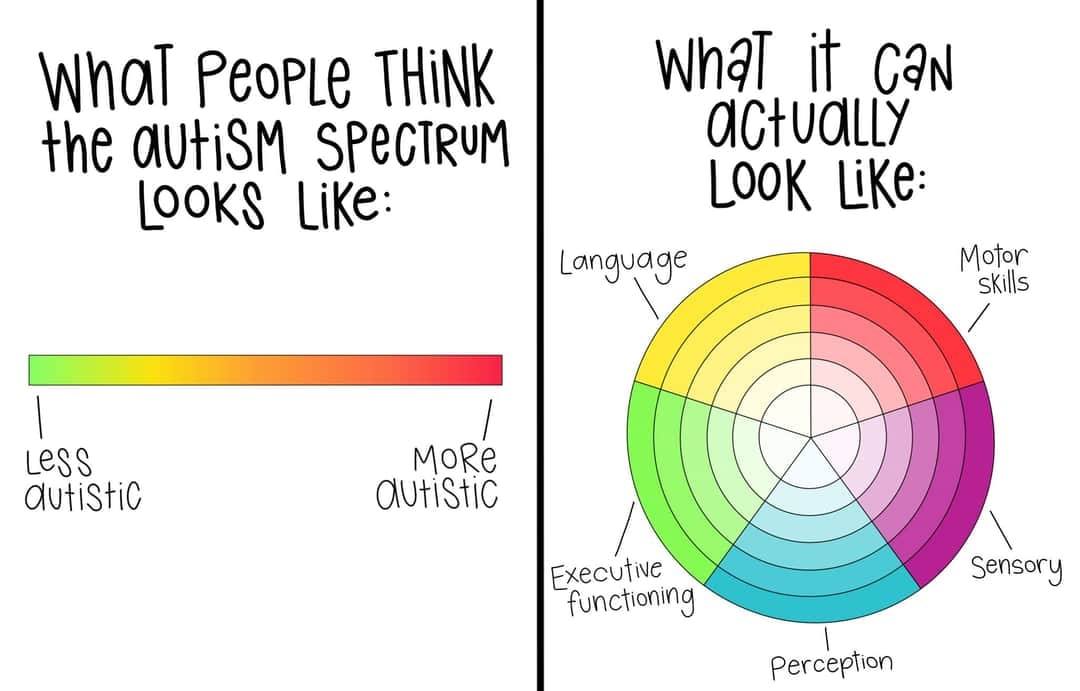

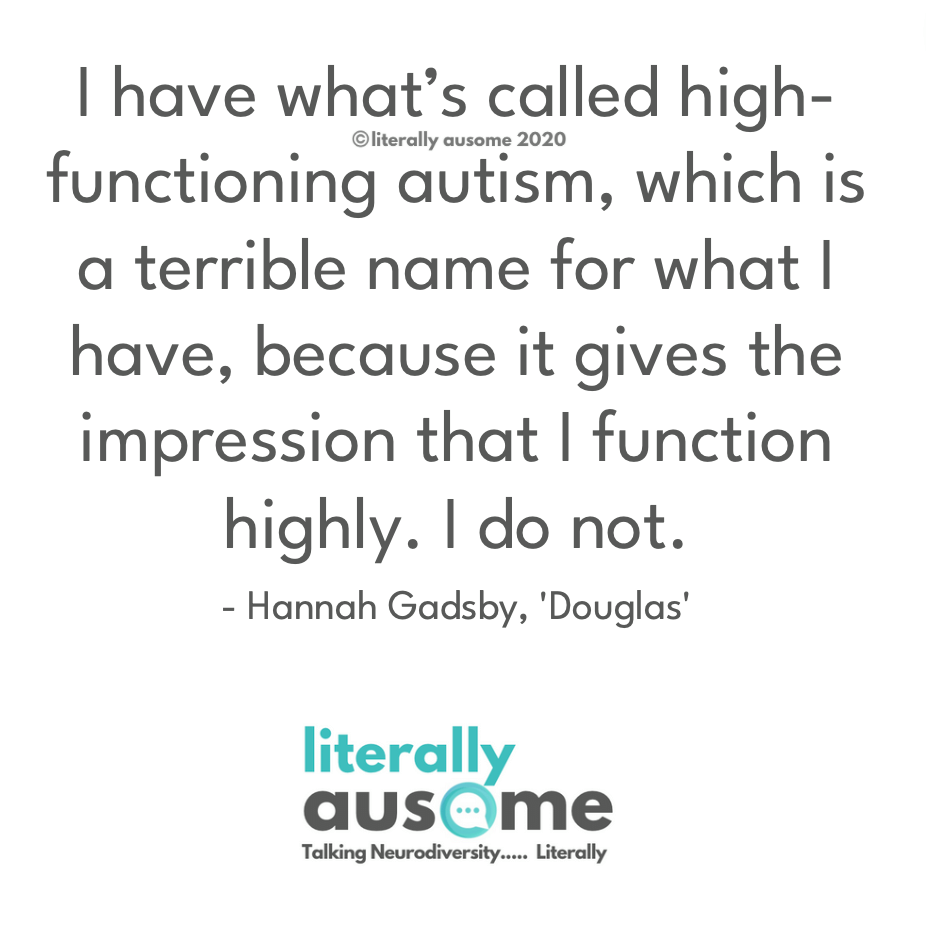

The way that the Autism Spectrum Disorder is portrayed is as a line (literally, a spectrum) that goes from 'less Autistic', to 'really Autistic'. (There are also those that describe Autistic people as either 'high-functioning', or being a 'high-functioning' Autistic, which assumes that the person is at the 'less Autistic' end of the spectrum. This is both wrong and insulting and there's more on this below.

Recently, the 'Spectrum' has been modified after the Autistic community expressed their concern over how misleading this linear association is and has been revised to be more like a gradient or colour wheel that now identifies the areas of strengths, challenges and traits associated with Autism, including social communication and executive functioning skills, and language and sensory challenges/differences.

An Autistic person might be able to plot or mark the colour wheel to illustrate their areas of difficulties or challenges, as well as strengths. However, it's important to keep in mind that these dots can move up or down each area of the colour scale every day - or even several times a day - depending on how affected or impacted the person is at any given time. For example, their sensory sensitivities are usually less impacted at home as they tend to have more control in their own environment.

The Autism Spectrum starts at Autism, not at neurotypical

Saying 'everyone's a little bit on the Spectrum' is not only incorrect and inaccurate, it's also really offensive to those that are Autistic i.e. those literally 'on the Spectrum'.

Six Myths about Neurodivergent Children

Neurodivergent children need to be taught social skills

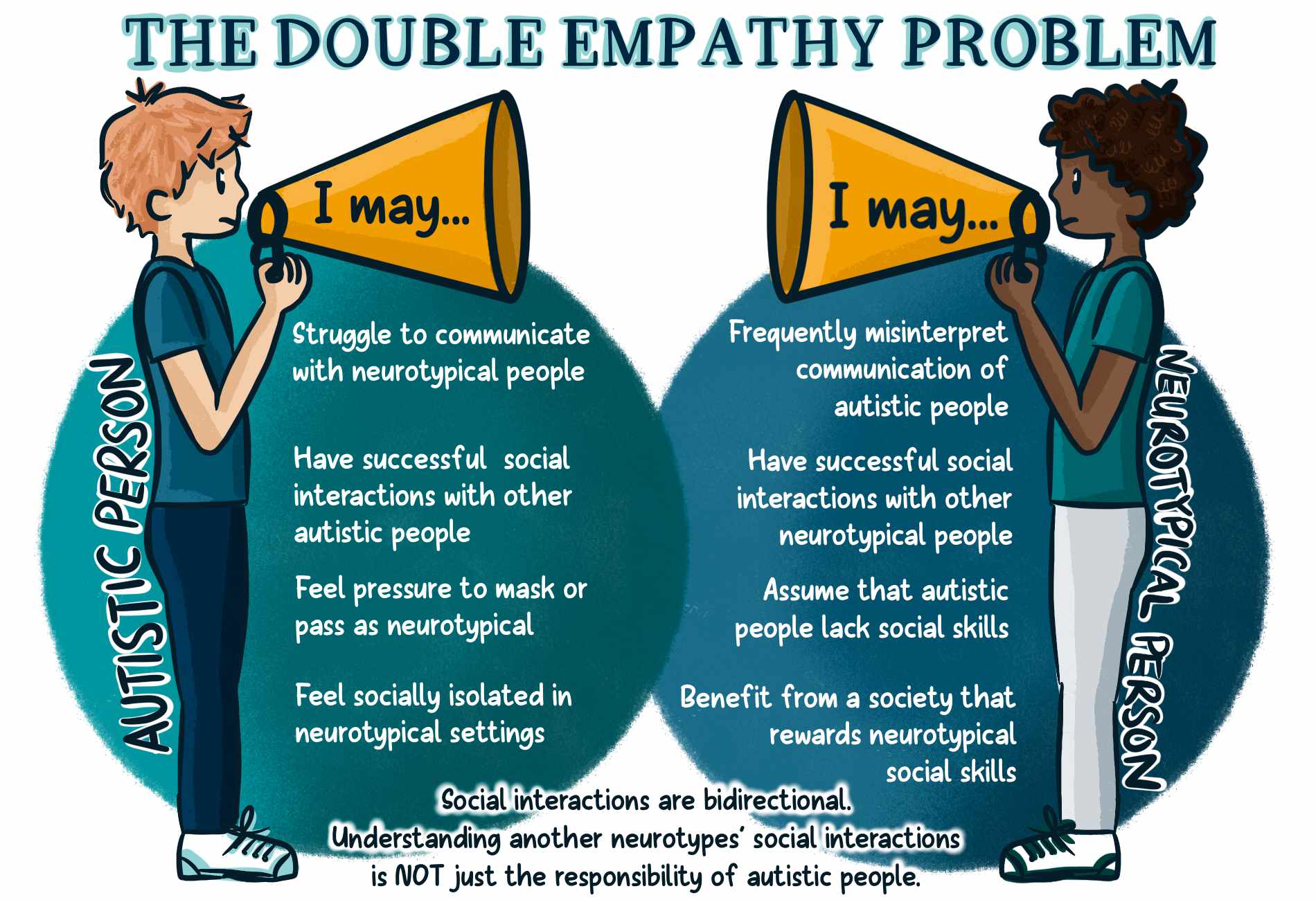

This is simply not true and current research supports this. Neurodivergent children have their own very effective ways of communicating but unfortunately are often misunderstood.

Neurodivergent children need to be taught how to interact with their peers

Also false! Neurodivergent kids are often othered and excluded by their peers and adults. This in itself shows that the issues do not lie solely with Neurodivergent children. You cannot make friends if nobody wants to be your friend or if other people do not understand you. Interacting, communicating and building relationships are all two-ways tasks and so everyone has a part to play in making these tasks a success.

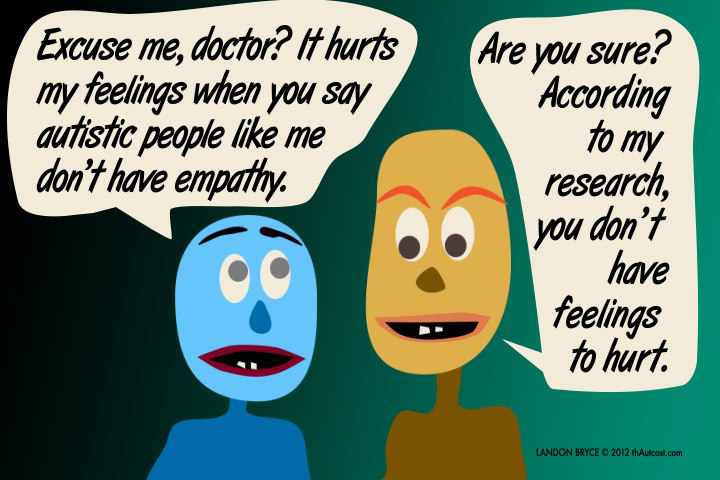

Neurodivergent children lack empathy

There is no evidence whatsoever to support this. In many cases, the opposite is true with Neurodivergent children experiencing hyper-empathy. There may be subtle differences in the ways Neurodivergent children express their empathy and this needs to be understood.

Neurodivergent kids are not as competent as their peers

This idea needs to be deleted from society. In order to meet Neurodivergent children with understanding then we must presume competence. This means that we presume Neurodivergent children are just as competent as their peers. This means that we allow for differences in communication styles, adapt our communication but mainly speak to Neurodivergent in the same way we do to their peers. We never make assumptions like “they wouldn’t understand”.

Neurodivergent children have difficulty learning

Everyone can learn but they need to be taught in ways that are compatible with their Neurotype. In fact, many Neurodivergent kids are excellent autodidactic learners. This means that they can teach themselves when given the opportunity to follow their interests.

Neurodivergent children need to be taught how to behave

Neurodivergent children know how to behave but often they experience such high levels of anxiety, stress and/ or trauma that people who are not informed about such things misinterpret their behaviour.

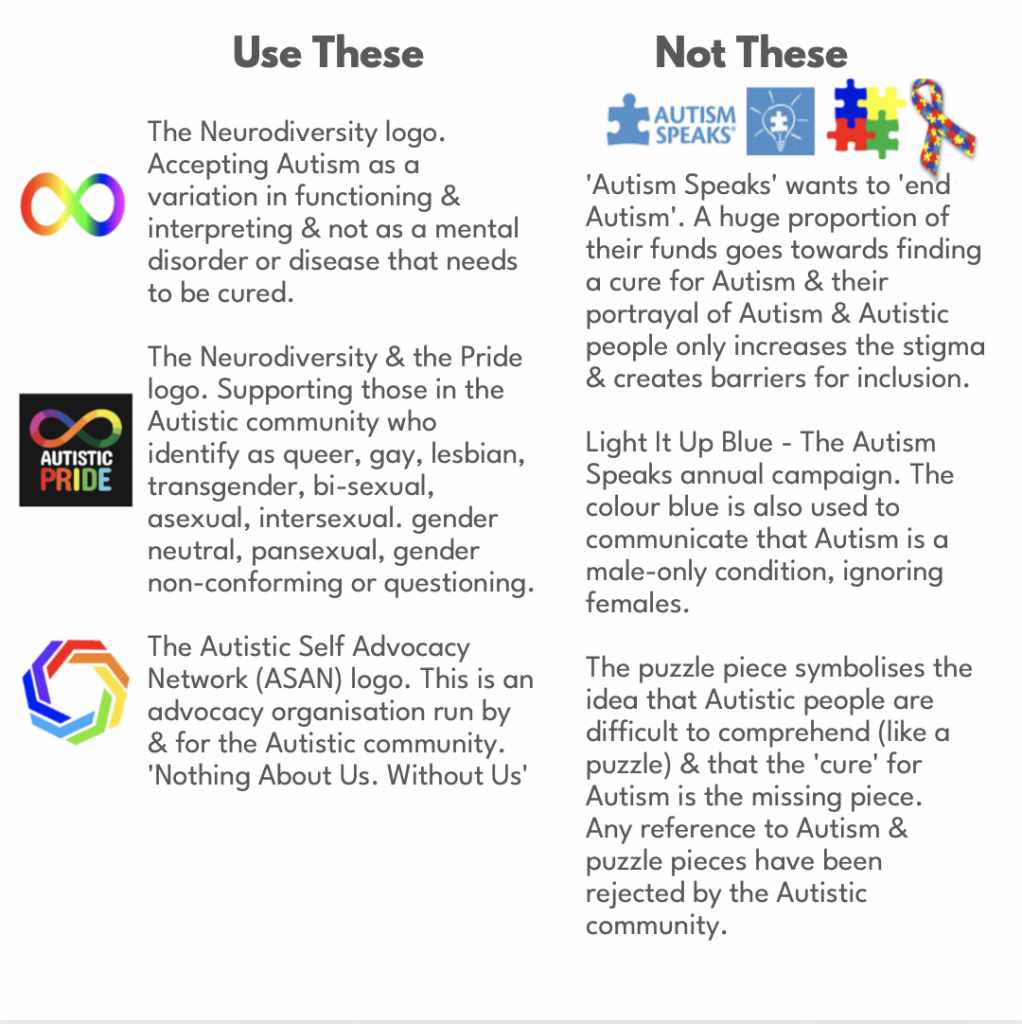

Autistic Symbols

It's really important to know which symbols to use when supporting your Autistic children and/or friends in your life.

In conclusion, the puzzle piece is better left in the box it came in than any association with Autism.