What is ARFID?

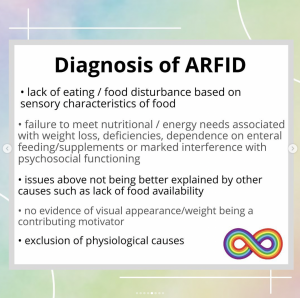

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) is a new diagnosis in the DSM-5 as an eating or feeding disorder characterised by a persistent and disturbed pattern of feeding or eating that leads to a failure to meet nutritional/energy needs. ARFID was previously referred to as 'Selective Eating Disorder', or 'Sensory Eating Disorder'.

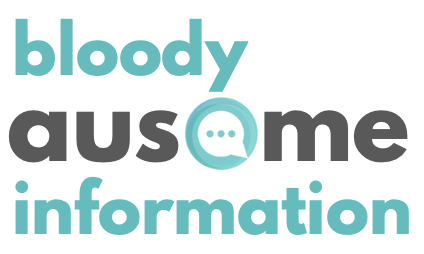

ARFID is similar to anorexia in that both disorders involve limitations in the amount and/or types of food consumed, but unlike anorexia, ARFID does not involve any distress about body shape or size, or fears of fatness.

Source: @infinityhypnosis, 'What ARFID is NOT'

Although many children go through phases of picky or selective eating, a person with ARFID does not consume enough calories to grow and develop properly and, in adults, to maintain basic body function. In children, this results in stalled weight gain and vertical growth; in adults, this results in weight loss.

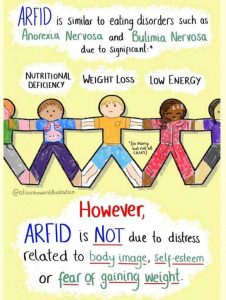

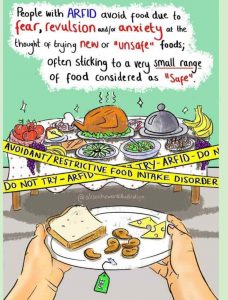

While picky eating and ARFID may have certain similarities, ARFID is differentiated by the level of physical and mental distress that eating causes. Someone with ARFID may have difficulty chewing or swallowing, and can even gag or choke in response to eating something that gives them high levels of anxiety. The anxiety can also cause them to avoid any social eating situation, such as school lunches or attending birthday parties.

Is it just fussy or picky eating or is it ARFID?

Although picky eating is common in children, and in most cases improves with age without the need for any intervention, this is not the case for children with this subtype of ARFID.

- It can be difficult to distinguish between picky eating and ARFID, particularly in children.

- Taking the approach of telling a child to ‘eat the food, or go to bed hungry’ may work with picky eaters but would never work for anyone with ARFID.

- ARFID sufferers aren’t just being stubborn, they’re often fearful of specific food colours, textures, tastes or smells.

- Forcing someone with ARFID to eat what’s in front of them may cause them to vomit, leading to a traumatic experience, which is likely to worsen the problem.

- Early research suggests that Autistic children are more likely to be in this category of ARFID.